While Sarah has her hands full in her new social work position, I’ve settled into a nice little groove here at home. Here’s a short – and very long overdue – report.

Garden

We’re having a cool summer, with temps mostly in the high 70s/low 80s, peppered by a few heat waves. Tomatoes planted in April are just now ripening, namely ‘Flamme,’ a French heirloom. Fruits are small to medium in size, about 3″, with orange skin and flesh, and are mild, but rich in flavor.

This is our second year growing ‘Black Beauty’ zucchini, another heirloom variety, and while it may not impress any summer squash aficianados, I’m liking it for two reasons: 1) the fruits are pleasantly flavorful and tender, even when large (12″), and 2) our consumption rate seems to dovetail with the plant’s production rate. No begging friends, family, neighbors, and total strangers to take zucchini; we harvest 2-3 fruit about every 3-4 days.

Contraptions built of PVC pipe and deer net/fence to protect the grapes and Bartlett pears from rats, squirrels and raccoons are working so far.

Bees

We had one of our worst seasons of losses last fall and winter, coming into this spring with only two hives. Sarah did splits, and we acquired a new colony from a fellow beekeeper in order to diversify our genetics. We’re now up to five colonies. We harvested honey from dead-outs in the fall and spring, but haven’t harvested much since, and I imagine we won’t have much of a summer harvest either.

Sadly, the specialty wine shop that carried our honey decided to close its doors after 130+ years of business. So, our relative slow pace of production hasn’t created any stressful consequences. In doing business with the wine shop, however, we entered the dark hole of business licensure and taxes. Unsurprisingly, we’re due to pay more in taxes than we will ever sell in honey or hive products. While we may have fantasized at one point about making a living keeping bees and selling hive products, we’ve long since realized that the scale of production necessary isn’t one we’re willing to pursue.

On the upside: five hives in two locations has made our beekeeping a little more manageable.

Canning

Our pantry dwindled while Sarah traveled and studied in Guatemala last summer, and gratefully, she’s been diligent in restocking it. She’s made apricot jam from farmer’s market fare, plum jam from our Santa Rosa tree, and pickles galore from our garden. We’re growing ‘Mini White’ and ‘County Fair’ pickling cukes, and have watered more frequently this summer to ward off bitterness. Both make a tasty pickle, with Mini White sweetening up a bit in either lacto-fermented or fresh-pack processes. We’ve decided we like the flavor of fresh-pack pickles better than lacto-fermented, but admittedly, we haven’t mastered the art of lacto-fermentation to a point of consistent results. Our lacto-fermented sauerkraut and cauliflower turned out well, but our pickles have been hit-or-miss.

Next up: white peach jam, courtesy of fruit from a client’s garden.

Brewing

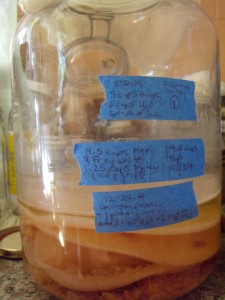

Sarah’s travels extended to Cuba last year, where she picked up honey from a few different sources. Her host Yaritza gifted her with two big rum bottles bought on the street. We suspect it had been thinned with water, since it began to ferment soon after Sarah returned home. Tragically, Yaritza was diagnosed with a brain tumor a few months later, and passed away after a surgery to remove it. In her honor, I hope, I made an orange mead, using ale yeast (Safale 05) for the first time.

Lately, I’ve been avoiding Campden tablets so as not to introduce unnecessary sulfites: instead, I gently heated the honey in water, bringing it to a near-boil, then letting it cool. I juiced the rest of the oranges and five Bearrs limes from our trees, which yielded about a gallon of juice. Raisins (a more natural alternative to yeast nutrient) and high-quality jasmine tea (to provide some tannins) rounded out the recipe. Since so many of my meads and melomels have seemed to need years of maturing, the inspiration to use ale yeast was to create a ready-to-drink mead. I still need to either rack it again, or go ahead and bottle it, so how ready it is remains to be seen.

Yesterday, I started a plum wine. I’ve been trying to use fruit from the freezer, and had a few gallon ziplocks of whole Santa Rosa plums, along with two 1.25 liter bottles of plum juice. To that, I added a few pounds of cut-up Burbank plums, a sizeable sprig of tarragon and a 2″ length of cinnamon stick, along with about 4 lbs of white sugar and about 3 lbs of honey. I used a yeast I haven’t tried before: RP–15 Rockpile, a yeast isolated in Syrah-making described as emphasizing fruity flavors. It’s always fun to experiment, and I’ve been looking for a good yeast for my meads and melomels that isn’t a champagne yeast or derivative.

Sarah’s vinegar-making has filled our cupboard with red and white wine vinegars, so I also started making shrubs – another great way to use freezer fruit. The best to date were a blueberry shrub with red wine vinegar and a peach raspberry shrub with white wine vinegar.

From my internet perusing, the general rule of thumb for shrubs is 2 cups fruit: 1 cup sugar: 1 cup vinegar, but I have found I like a less sweet, more vinegary drink, so I add less sugar during the maceration period, then more vinegar to taste during the maturation or rest period. The process timeline varies according to different websites, for example, how long to macerate the fruit and sugar, as well as how long to steep the mixture in vinegar after maceration. Another variation includes whether to add vinegar to the sugar and fruit mixture or whether to add it to the strained syrup (from the fruit and sugar).

The ultimate difference might be in the health benefits rather than the flavor: no matter which process you use, the end result is a uniquely tasty, refreshing drink. If you’re using unpasteurized vinegar, like we do, I imagine the health benefits remain stable, but that’s just a guess. We didn’t intend to jump on the hipster shrub bandwagon here, we just had all the raw ingredients at hand, and plenty of them: fruit, sugar (honey) and vinegar.

Cheers!