As I write this, five jars of red and white wine vinegar and their vinegar mothers sit in jars in the kitchen, working away. I grew all of the vinegar mothers from scratch last summer, experimenting with various mixtures of grape mash, water, sugar, and honey.

Last August, I wrote about the confusing and contradictory information on making homemade vinegar. I fretted over whether my batches of vinegar from store-bought mother and from scratch would turn out. Vinegar making seemed like a strange and complicated science experiment.

9 months later, I can say with conviction that vinegar is indeed a wild science-y miracle as, I suppose, are most culinary and propagation endeavors. But making vinegar is also pretty easy, requires little time on the human’s part, and produces fabulously tasty results.

Here are the most important lessons I’ve gleaned from my first 6+ rounds of vinegar:

- Fruit flies rock. I initially read conflicting opinions on the importance of allowing fruit flies to colonize the vinegar concoction when one is trying to raise a vinegar mother from scratch. Short answer: almost all of my jars of fruit, water, and sweetener quickly grew beautiful vinegar mothers in the presence of swarms of disgusting little fruit flies. The flies’ magic comes from the vinegar-making bacteria on their feet. Once you have a vinegar mother established, there’s no need to include fruit flies in the jar for future batches of vinegar.

- Making white wine vinegar is harder than making red wine vinegar. Virtually all of my red wine vinegars taste amazing. Not so with the white wine vinegar. The mothers appear less robust, and the vinegar sometimes tastes a little ‘off’. Maybe I’m still acquiring my taste for the real deal? Since white wine is higher than red in naturally occurring sulfites, it’s more difficult for the Acetobacterium that turn wine into vinegar to flourish. I generally use wine that has no added sulfites for this reason, but have found that my vinegar mother readily turn ‘regular’ red wine into vinegar with no problem. Perhaps the subprime Acetobacterium conditions caused by the higher sulfites in white wine also explain why my white wine mothers have been more prone to molding. But more on that next…

- Neglect your vinegar mothers too long, and they will mold. After bottling finished vinegar in December and feeding the mothers their wine/water mixture, I got busy and didn’t tend to the jars until mid-April. While the majority were still doing fine, some of the smaller jars of white wine vinegar had grown flamboyantly colorful mold patches and had to be thrown out.

- One of my biggest points of confusion when I started this project was how long it takes for the mother to turn the wine into vinegar. I now know that it takes about a month for a new layer of mother to form on top of the wine, indicating that the vinegar is ready for consumption. Timing definitely depends on the size of the mother in relation to the amount of liquid you add. It will take a small mother longer to digest the alcohol in a comparatively large amount of wine. However, once your mother has finished her first batch of wine in a given jar, she should be able to complete the next batch in the same sized jar in about a month.

- Darkness isn’t required for vinegar mothers to do their thing. As with most of my projects, I’ve become lazier and relaxed my standards over time. In the beginning, I thought vinegar mothers needed total darkness to be happy. These days, my ladies live in glass jars on top of the refrigerator (for warmth), and I’ve scrapped trying to swaddle them in towels to keep them in the dark. They’re growing just fine.

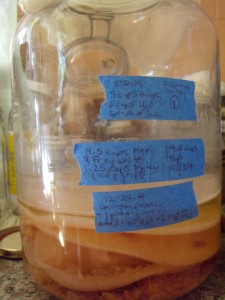

My happiest (and only remaining) white wine mother. I keep my ‘vinegar records’ written on painter’s tape on the sides of the jars.

I love the layers of mother that build up in the jar over time. If I were in the business of maximizing my vinegar production, I would be diligently dividing these pieces of mother to start new production jars.