This morning our top-bar hive swarmed, settling in the nearby camphor tree on a branch about 20 feet off the ground over the neighbors’ yard. We panicked of course, unsure what to do first and acutely aware of the possibility that the bees would pick up and leave before we could collect them.

A beekeeper recently told us he’s had luck getting swarms to stay put by slowly clanging metal on metal. He speculated that the bees are drawn to the vibrations. I grabbed a kitchen pot and ladle and pounded away, while Kelly brought a ladder to set up against the back of our neighbors’ house (and earplugs for herself).

Then we looked up and realized just how high up in the tree the bees were. We decided to call for backup. We lucked out; our good friend (and president of the Beekeepers Guild of San Mateo County) Rick Baxter arrived less than twenty minutes later with all of his awesome swarm-catching paraphernalia in tow.

As it turned out, though, our bee drama was far from simple. We were able to use Rick’s swarm bucket duct-taped to a long PVC pipe to shake down and capture most of the bees from their branch. Unfortunately, after dumping them into a hive in our garden we noticed two disturbing things: first, a large number of bees still buzzed around the branch in the camphor tree, and second, the bees already in the hive gradually moved out the entrance and took off again, heading toward the same neighbors’ front yard.

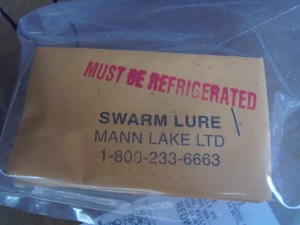

Rick brought out the big guns: a vacuum cleaner that sucks the bees down the long PVC pipe into a wood box, where their fall is cushioned by crumpled paper towels. By the time we got the leftover bees in the camphor tree into the hive, it was apparent that the original group was on the move again.

We stood in the neighbors’ yard and watched as the cloud of bees formed a new cluster on a juniper branch. Another ladder set-up and a good strong shake into the pole-mounted bucket, and we were able to bring these bees back to the hive. Our best guess was that we had missed the queen in our first capture and that the bees had taken off in search of her.

As it turned out, the story was a bit more complicated. As the bees clustered on the outside of the hive, we spotted the queen in the crowd, and Rick nudged her gently toward the opening of the hive. Once the queen is inside, everyone else will follow. But moments later we spotted a second queen, and then a third. In the constantly moving mass of bee bodies it can be hard to know for sure if you’re counting the same queen more than once, but we are confident that we counted at least three individual queens, more likely four to six.

This is extremely unusual, but it happened to us last year as well, and we’re concluding that we have some strange bee genetics going on. Ordinarily, a hive will raise multiple queen bees, and the queens fight to the death at birth. The victor becomes the hive’s new queen.

Last June, we found at least eight queens in a single swarm, and though we asked every beekeeper we knew and posted queries on the guild’s beekeeping forum, we found no one who had ever witnessed such a swarm. The hive that swarmed today was originally part of that multi-queen swarm, and it appears the genetics have been passed on.